A Tale of Two Players: Baseball Legends in Humboldt, Kansas

May 29, 2020

Most small towns will never produce even one famous athlete.

Humboldt, Kansas, can claim two.

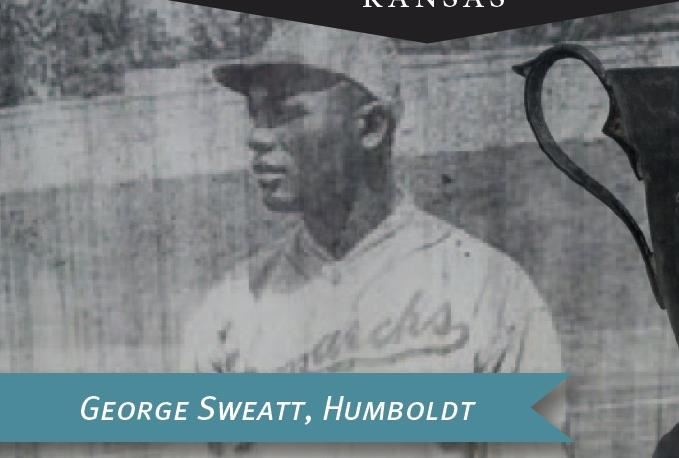

The southeast Kansas community of about 2000 people is the hometown of two famous baseball players: Walter “Big Train” Johnson, one of the most revered pitchers of all time, and George “Sharkey” Sweatt, a combination infielder and outfielder known for his wicked hitting who played for the renowned Kansas City Monarchs of the National Negro League.

Humboldt is a town that loves its sports, and the community “is pleased as punch” to share the two men’s stories with a wider audience as part of the Hometown Teams Smithsonian exhibition, said Humboldt Historic Preservation Alliance mentor Eileen Robertson.

Sweatt and Johnson share an incredible achievement. Each man won the World Series with his ball club. Sweatt and the Monarchs took the first-ever Negro League World Series, while Johnson’s Washington Senators won in his eighteenth year with team.

Even more incredibly, they won their respective World Series in the same year—1924.

But for Sweatt and Johnson, winning wasn’t everything. More than great ballplayers, both were well-known league gentlemen who took sportsmanship seriously, nurturing deep roots in their Kansas communities.

Even more incredibly, [Johnson and Sweatt] won their respective World Series in the same year—1924.

Sweatt was a devoted schoolteacher in Coffeyville, Kansas, south of Humboldt. If the baseball season overlapped with his teaching duties, there was no question which he would pick, according to Negro Leagues baseball historian Phil Dixon in this article by Mark Schremmer: ”Sweatt was kind of an academic and a ballplayer,” Dixon said. “He….would leave the team early enough so he could go teach. He was a tremendous individual.”

Johnson is also remembered for the polite disposition that accompanied the terrifying power of his arm. Sometimes he would even throw easier pitches to opposing players with low batting averages.

Although the two men never played ball together, their shared origins in Humboldt link them together in baseball history. And the town thinks it’s important that their hometown heroes’ stories stick around.

“[The] HHPA knows that all history not promoted and preserved is lost,” Robertson said.

To keep that from happening, Humboldt set up a local baseball Hall of Fame with a display featuring photos, articles and memorabilia associated with the two men. Town teams play at both Walter Johnson Field (baseball and football) and at Sweatt Field (baseball), and monuments to both men stand at various locations throughout town.

While Johnson is better known, Sweatt has garnered renewed attention in recent years. Humboldt’s residents realize how easy it would be for him to remain in Johnson’s shadow, so the town is taking steps to publicize Sweatt’s rich history in the area.

He was the first African American letterman at what is now Pittsburg State University, where he was a talented track and field star, and a plaque marking the place of his birth is planned—fitting recognition for the man whose autobiography includes a dedication to “the older citizens of Humboldt, Kansas for accepting me for what I was and have become.”

This blog post was part of a series of sports history essays written for the Hometown Teams Smithsonian Institution traveling exhibition in 2015.