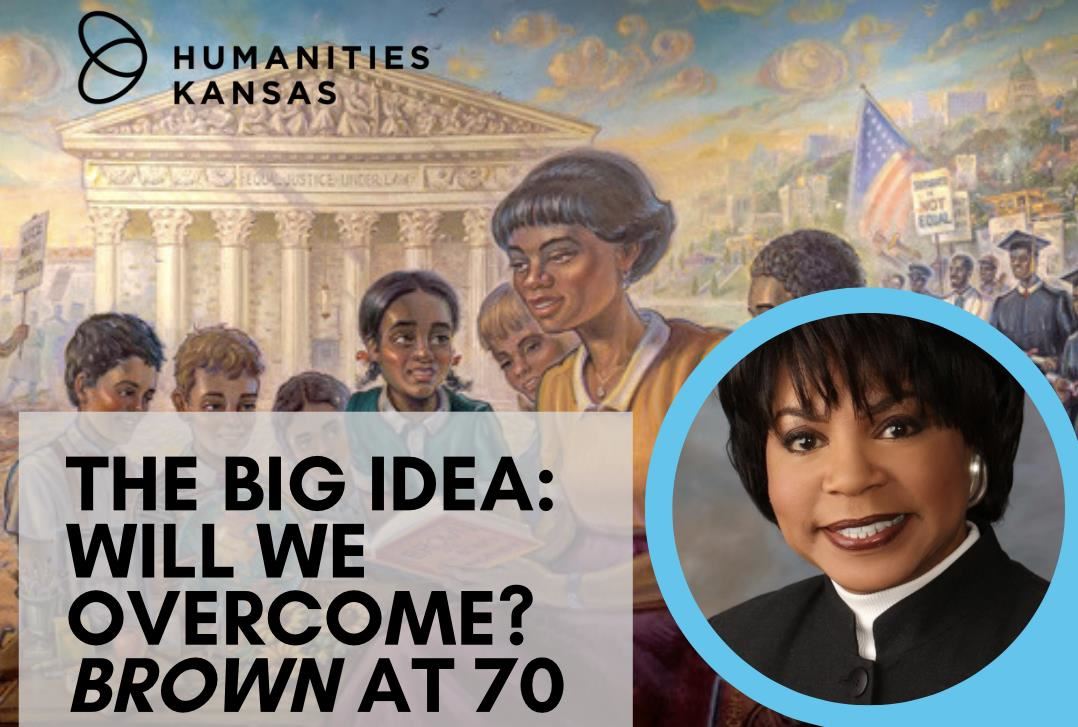

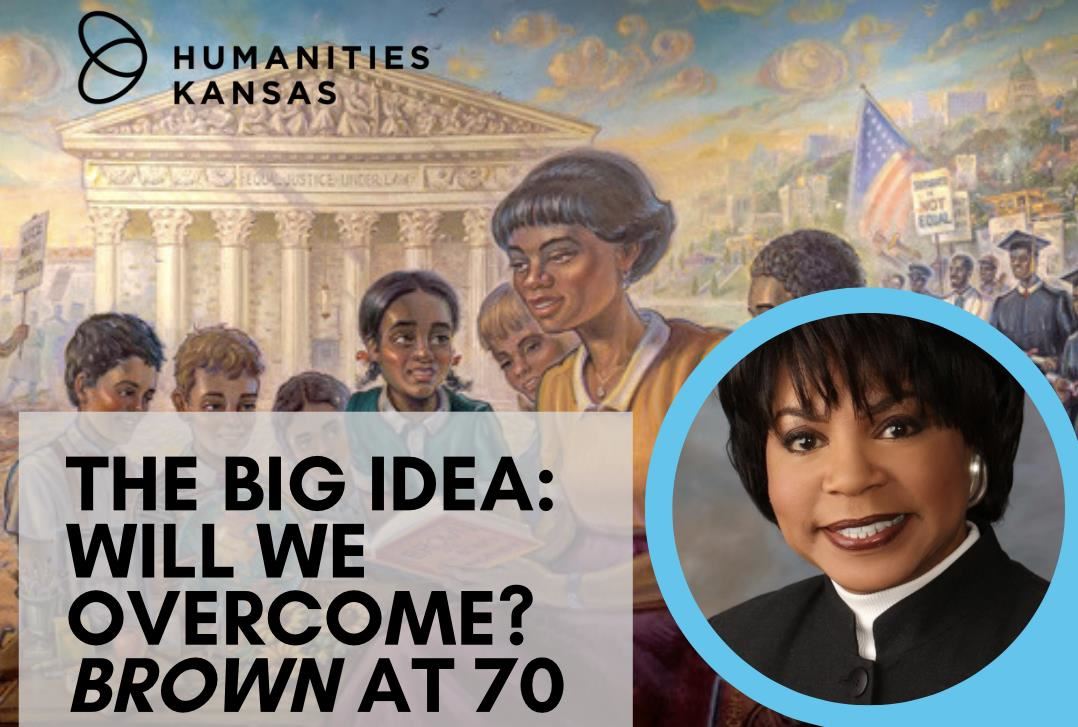

Big Idea: Will We Overcome? Brown at 70

January 3, 2024

Watch Cheryl Brown Henderson's Big Idea

Cheryl Brown Henderson is the Founding President of the Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence, and Research and the daughter of the late Rev. Oliver L. Brown, lead plaintiff in the Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka case.

In 1950 my family became part of the campaign to end racially segregated public schools. History literally knocked on our front door when Charles Scott, a childhood friend of my father and an attorney for the Topeka NAACP, asked him to join their efforts to take the fight against racially segregated public schools to federal district court. After some deliberation my father accepted his friend’s impassioned invitation, becoming one of 13 parent plaintiffs collectively representing 20 children. Each parent attempted to enroll their children in nearby white-only elementary schools. This simple act became my parents’ journey into civil rights history.

The Topeka NAACP case was filed as Oliver L. Brown et al vs. the Board of Education of Topeka, with my father as lead plaintiff.

We, like all involved in this case, were a traditional Kansas family; at the time, my parents were raising two small girls and awaiting the arrival of a third. While the case worked through the courts, my parents remained busy with family activities and meetings about the litigation. During this period my father was a welder for the Santa Fe railroad while working toward ordination in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. In 1953 he became Pastor of St. Mark AME Church in North Topeka. Years later he would pastor Benton Avenue AME Church in Springfield, Missouri.

On May 17, 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren announced the U.S. Supreme Court opinion in what is colloquially known as the Brown decision, finding racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. In addition to Topeka the ruling encompassed similar cases from Delaware, South Carolina, Virginia, and Washington, DC. Not until my sisters and I became adults did we fully comprehend what the court decision meant for our family and the nation.

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the Brown decision. The court’s ruling compelled the United States to reckon with its past and confront the unfulfilled promise of equality articulated in our founding documents. Seventy years later, it is a process still unfolding.

After the Brown decision, in an effort to comply, some school districts changed their attendance boundaries, while others began busing children away from their home neighborhoods. Historically, African American families bore much of the responsibility for desegregating public schools. Unfortunately, segregated African American schools were often closed, and African American teachers often lost their jobs.

Today many public schools that primarily serve children of color and/or children from low-income communities continue to struggle. Our nation has yet to live up to the tenets of the Brown decision. Some public schools are even on the verge of collapsing under the weight of an antiquated system of school finance in areas where there are pockets of poverty and racial isolation in urban communities. How can we expect public school teachers, principals, superintendents, advocates, and allies to ensure academic achievement within a system heavily influenced by social stratification? Ironically, the 14th amendment precedent set by Brown v. Board of Education has more resonance within other sectors of society, such as public accommodations and public spaces.

On the cusp of the 70th anniversary of the Brown decision, it is important to remember the declarative statement within the ruling that speaks to the monumental significance of education and reminds us that education is foundational to our democracy.

Today education is the most important function of state and local governments... It is the very foundation of good citizenship. Today it is the principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional training and in helping him adjust normally to his environment. In these days it is doubtful that any child can be reasonably expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right, which must be made available to all on equal terms.

The question remaining is, How do we use our political apparatus in ways that bring people together, not ways that deepen the hierarchies within our communities? In order to form that “more perfect union,” the first step requires having direct, honest, and candid conversations that link the past’s inequalities to the present’s conditions.

Race, ethnicity, and gender equality still matter. They influence opportunities and outcomes throughout society and every level of government. We must use our vote and our voice to challenge the status quo of racial, ethnic, and gender disparity and fight for social justice. Until we do that, we will continue pondering why, 70 years after Brown v. Board of Education, our society and our schools remain separate and unequal.

Spark a Conversation

-

ENGAGE - 2024 is the 70th Anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education. Commemorate this milestone with FREE resources from Humanities Kansas, including Speakers Bureau talks, the Big Idea, and special grant opportunities.

-

VISIT The Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park in Topeka tells the story of “everyday people coming together for a common goal to carry the country toward true equality” through exhibits and events.

-

WATCH The 2014 StoryCorps series of interviews featuring former students, teachers, and Topeka community members who lived through the momentous Brown v. Board decision.

-

EXPERIENCE the Big Idea with others. The West Wyandotte Library in Kansas City (Kansas), the Topeka & Shawnee County Public Library, and the Advanced Learning Library in Wichita are live-streaming the Big Idea with Cheryl Brown Henderson at their libraries on Friday, January 12 at Noon. It's a great opportunity to spark an in-person conversation with others.