Civil Rights to Correct Civil Wrongs

August 10, 2018

Civil Rights activist Ron Walters once called his Wichita hometown the “Mississippi of the North.” He had good reason to think so. During the 1950s Walters lived in a Wichita that denied the black population the right to swim in the municipal pool and admittance to the city parks. The local hospital forced blacks to be treated in a separated wing, and ninety percent of Wichita’s African American population lived in seven census tracts. Children attended segregated schools through the eighth grade, and hotels, restaurants, and movie theaters did not serve black patrons unless the movie theater had a balcony for blacks to sit or unless a restaurant was black-owned.

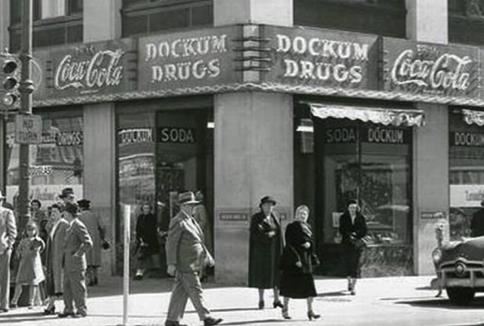

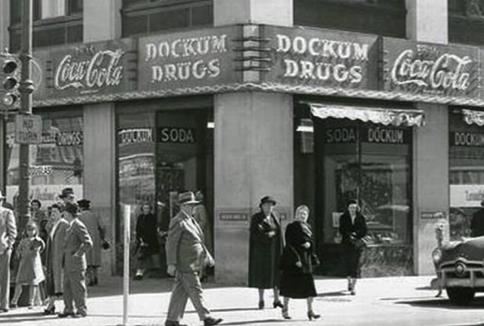

The latter proved to be the final indignity for Walters and his cousin Carol Parks. Parks recalled the humiliation of standing at a lunch counter waiting to be served food which she was forced to eat elsewhere solely because of the color of her skin. “We never knew what it was to just sit there and have a glass and dishes,” she remembered. This treatment sparked Parks and Walters, members of the NAACP youth group, to plan a sustained sit-in of a family-owned drugstore chain in downtown Wichita—Dockum Drugs.

The carefully planned protest began on a hot and humid Thursday evening in July 1958. A dozen young people quietly walked into the downtown location at the corner of Broadway and Douglas late in the afternoon and asked to be served. Parks seated herself first and was about to be handed a coke when the waitress noticed her companions and said, “you are not colored are you dear?” When Parks answered yes, the waitress cited store policy and refused to serve her and her fellow protestors. The young people, ages 15-22, quietly sat facing forward as if expecting to be served until the store closed later that evening while anxious parents watched from across the street. That day a movement began.

The group organized the sit-ins for three days a week—Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. The strategy, recalled Walters years later was to “shut off the flow of dollars.” The youth group committed themselves to returning to the drugstore for as long as it took to be served. They received the support of the Wichita NAACP, but not that of the national office, which cited that direct action was against policy. The national office preferred litigation.

Walters knew the sit-in hurt Dockum’s business when protestors took to the lunch counter stools because the manager occasionally closed the counter as a way to refrain from serving the black students. Other times white patrons walked into the store and immediately left without making a purchase once they noticed the protesters.

Nearly three weeks after the protest began on the afternoon of August 11, the owner of the Dockum chain walked into the store and saw Parks sitting at the counter. He threw up his hands and called to his store manager, “serve them—I’m losing too much money.” Shortly thereafter all the Dockum stores in the city were integrated.

"You are not colored are you dear?"

Buoyed by its success, the group proceeded to protest at other Wichita establishments. For the next five years they sat in and picketed carrying signs proclaiming “Stop before You Shop,” Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work,” and “Don’t Put Your $ in Cash Registers That Your Hands Can’t Ring.”

Humanities Kansas awarded a Humanities For All grant to Storytime Village, Inc., of Wichita to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the sit-in with a traveling exhibit titled “People, Pride, and Promise: the Story of the Dockum Sit-in.” According to project director Prisca Barnes, the exhibit will explore how this “early Civil Rights Era lunch counter protest helped to shape and transform the struggle for racial equality in America.” Barnes also presents the "Dockum Drugstore Sit-in" topic in the new Movement of Ideas Speakers Bureau catalog.

Join the Movement of Ideas

- Commemorate: Attend the Dockum Drugstore Sit-in 60th Anniversary on Saturday, August 11 from 10am to 1pm at the Chester I. Lewis Reflection Square Park, 205 E. Douglas in Wichita.

- Spark a Conversation with Clarence Lang's Big Idea: It's Time to Change How We Talk About the Civil Rights Movement or by reading "Dissent in Wichita: The Civil Rights Movement in the Midwest, 1954-72" by Gretchen Cassel Eick.