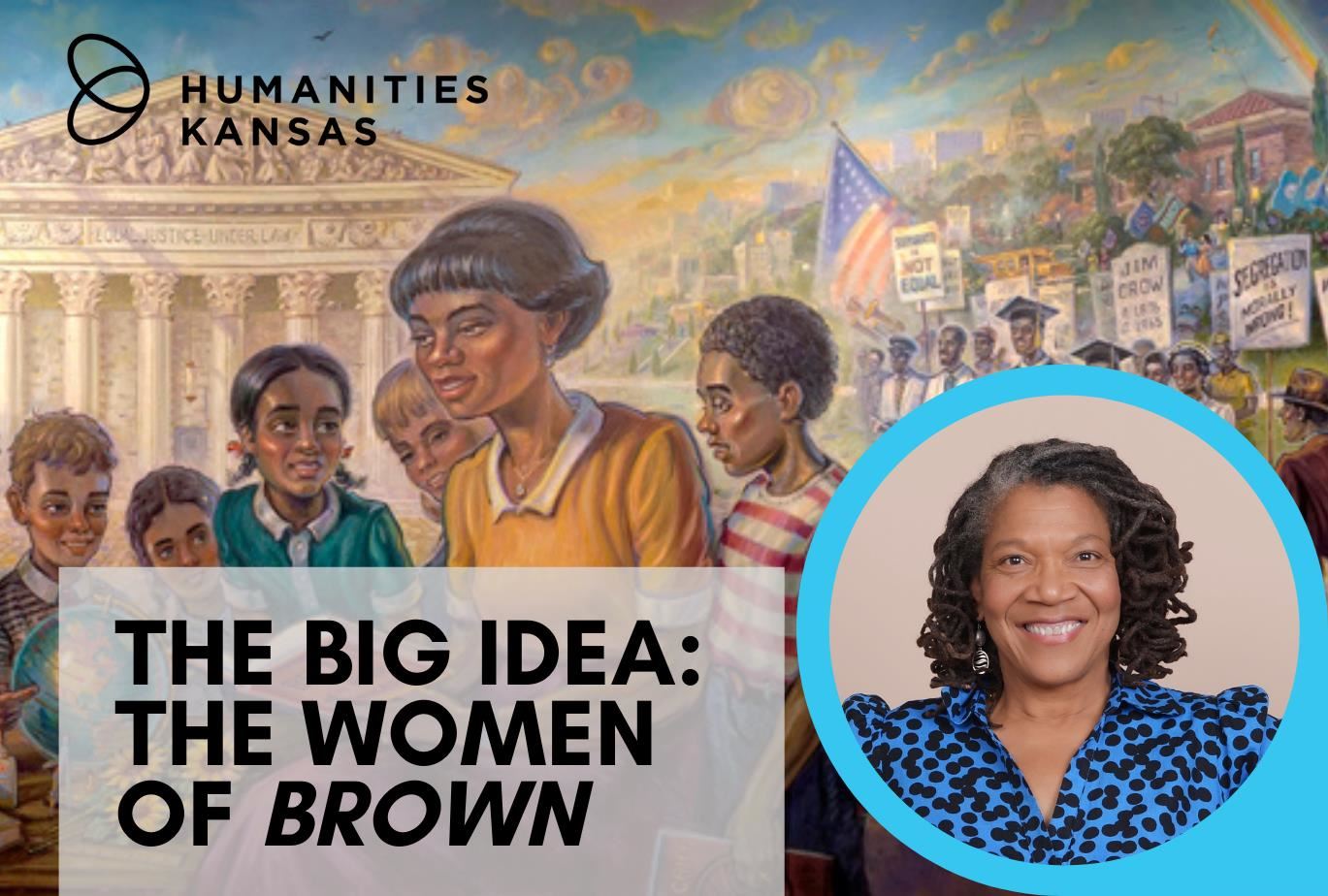

Big Idea: Rectifying "et al." History: The Women of Brown Project

February 1, 2024

Donna Rae Pearson holds a Master’s degree in History from Wichita State University and specializes in Public History. She is a museum specialist at the Kansas Historical Society. Prior to working at KHS, she was the Local History Librarian at the Topeka & Shawnee County Public Library, where she taught people how to conduct research and worked to preserve the stories of the Topeka community. She is also a commissioner on both the City of Topeka’s Local Landmarks and Planning Commissions and a board member for the YWCA of Northeast Kansas in Topeka.

“The movement of the fifties and sixties was carried largely by women…”

-Ella Baker, Civil Rights Activist

For too long, the Brown v. Board of Education case has been remembered as a fight led by men in suits. But the truth is that the case is titled Oliver Brown, et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, et al. The “et al.” listed after Brown signifies twelve Black, seemingly ordinary women from Topeka, Kansas, who also played a crucial role in the landmark victory. These mothers agreed to be plaintiffs, pushing for equal access to educational opportunities for all Black children, not just their own.

The twelve women represented a range of experiences. Most of the “et al.” women of the Brown case—“et al.” meaning “and others” in legal jargon—grew up in small rural communities in Kansas and probably attended integrated schools. Lucinda Todd was 48 at the time the lawsuit was filed. A college graduate and NAACP leader, she fought for her daughter Nancy to be able to participate in school music education. Darlene Brown was less formally educated and only 24 in 1951, the year the case was filed. Maude Lawton was from a small town in the Creek Nation in Oklahoma. Iona Richardson landed in Kansas from Wisconsin. There were family relationships amongst the twelve: Shirla Fleming and Vivian Scales were sisters. Alvin Todd, Lucinda Todd’s husband, was a cousin to plaintiff Zelma Henderson. Of the twelve women, it appears all but one worked outside of the home in order to contribute to the economic stability of their families. All were married at some point between the time they tried to enroll their kids in a nearby white school until the announcement of the Supreme Court decision three years later.

Lucinda Todd (right) with husband Alvin and daughter Nancy. Image courtesy of the Kansas Historical Society.

Their activism was not a sudden awakening. During the Jim Crow era, Black communities built their own institutions—social, political, spiritual, and economic—as a response to segregation. Kansas practiced both de jure segregation—segregation imposed by law—and de facto segregation, which was imposed in practice even when it was not required by law. It was in these segregated spaces of Topeka that these women honed their leadership and organizational skills. Black churches and clubs served as training grounds. Social networks, the lifeblood of their communities, fostered open discussions and strategizing. Their everyday connections became their quiet strength.

The women of Brown had influences beyond the Brown, et al. v. Board court case: they were one of the sparks of the modern Civil Rights Movement. By dismantling the Supreme Court’s racist Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1898, which codified separate but equal, they paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Why have their names been lost in the history books, hidden behind a simple “et al.”? The biases. Bias in the media. Bias in history itself. Bias in community memory. Due to these biases, Black women's accomplishments have long been minimized, overshadowed, and even erased. The Women of Brown Project is working to change that. By telling the stories of these remarkable women, we honor their legacy and show the world that social change often starts with everyday heroes. Their story matters today more than ever. They show us that change does not come from grand speeches or single events but from the tireless efforts of ordinary people creating pivotal moments. By remembering these twelve mothers, we inspire future generations to fight for what is right, reminding them that even the smallest voice can make a difference.

They say a person will not die if someone says their name. To honor these women, please say their names:

Darlene Brown

Lena M. Carper

Sadie Emmanuel

Marguerite Emmerson

Shirla Fleming

Zelma Henderson

Shirley Hodison

Maude Lawton

Alma Lewis

Iona Richardson

Vivian Scales

Lucinda Todd

These twelve Black women proved that ordinary people, united by a common goal, can indeed change the world.

Spark a Conversation

- READ Books and articles that bring new light to the women of the Civil Rights Movement. Authors Paula Giddings, Darlene Clark Hine and Kathleen Thompson, Janet Dewart Bell, Rachel Devlin, and Jacquelyn Dowd Hall have expanded this important history.

- INVITE Donna Rae Pearson to present her Speakers Bureau topic your community. Commemorate the 70th anniversary of Brown et al. v. Board of Education with FREE resources from Humanities Kansas, including Speakers Bureau talks, the Big Idea, and special grant opportunities.

-

EXPERIENCE the Big Idea with others. The Topeka & Shawnee County Public Library, and the Advanced Learning Library in Wichita are live-streaming the Big Idea with Donna Rae Pearson at their libraries on Friday, February 9 at Noon. It's a great opportunity to spark an in-person conversation with others.