The Intangibles Book Club

November 1, 2019

This essay is part of the Ad Astra: Working Hard in the Heartland initiative featuring the stories of working Kansans.

Story and Photos by Allie Crome

After 23 years of teaching, Kirsten Cigler-Nelson has heard the refrain plenty of times: “I can’t wait to graduate and move out of Kansas.” But Cigler-Nelson has spent her entire teaching career as an English teacher, including student teaching, in Kansas, at Topeka High in the USD 501 school district. In fact, she’s even been in the same classroom for that entire time.

“Part of what has kept me there that long is that it has always been a unique opportunity for me, that I maybe wouldn't get somewhere else,” Cigler-Nelson said. Teaching at Topeka High is special, she said, because the student body is so diverse, both in terms of race and socioeconomic status.

Nearly a third of Topeka High students are Hispanic and 16 percent are African-American, according to the Kansas Department of Education. Cigler-Nelson has taught students that worked three jobs while going to school just to make ends meet and other students whose parents could pay for everything.

“There's an energy from that that I love,” she said. “I also think it's a pretty accepting place. You know, there is something for everybody there, whether you're a teacher or a kid, and I don't know that every district is like that, that every high school is like that.”

Cigler-Nelson is soft-spoken, but intense. She expects a lot from her students, but in return, she’s a mentor, encourager and an advocate.

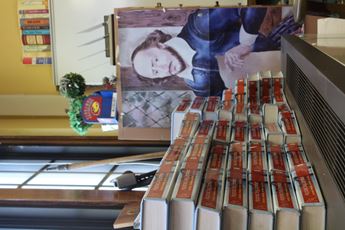

Even the very walls of her classroom reflect that relationship with her students. Several years ago, she received the go-ahead to paint her classroom and she enlisted the help of her students over the summer. Her students answered her call and came to paint the classroom a light, inviting yellow and inscribe favorite literature quotes on the walls. Lines from Slaughterhouse Five, The Importance of Being Earnest and more adorn the classroom, along with student projects and portraits of former students.

“After staying somewhere for a long time, especially in the same classroom, it’s hard to leave,” she said. “[Teachers are] inhabiting a place, you know,” she said. “It takes root in your heart and it’s hard to go.”

In Kansas, 16 percent of teachers leave the profession each year, according to a recent study by the Learning Policy Institute, a nonprofit that works with educators, researchers and communities on education policy and practice. That’s the 17th highest turnover rate in the U.S. The study cites low pay, burnout, and lack of support as the driving factors in teacher turnover.

On average, teachers in Kansas make $49,000, while teachers in neighboring states earn an average of more than $50,000, according to the Kansas National Education Association. Teachers in rural or low-poverty districts make less than that average, and as a result, experience shortages of qualified teachers.

As a newly-minted teacher about to embark on my first year in a Kansas school district, I wanted to know what keeps a teacher in the profession when burnout rates across the country are so high. When so many of my peers talk about wanting to get out of the state, it’s more important than ever to find reasons to stay.

Cigler-Nelson, who was born in Lawrence and has lived in the state her entire life, says she has “no intention” of ever leaving.

For Cigler-Nelson, the “intangibles” of teaching, including the community and the experiences, outweighed any potential downsides and have helped keep her in the profession.

Over the last several years, Cigler-Nelson has also noticed a rising momentum in Topeka, including students starting to see that there’s a place for them there. “You're seeing more kids actively involved in our city government,” she said. “I think there's a place now for younger kids to pick up and they're starting to see that if they involve themselves that things can change.”

She’s had students become involved in local government, work with initiatives to revitalize downtown and take part in a thriving arts community. Students have also started to return to Kansas after leaving for several years, Cigler-Nelson said. Those opportunities, coupled with the changing education landscape in Kansas, help Cigler-Nelson show students that there’s a place for them in their home state.

Cigler-Nelson hopes that out-of-the box thinking will be rewarded in education, as well as the continuing move towards more flexibility in the classroom. “Shifting away from the prescriptive nature of things is helpful,” Cigler-Nelson said. “It helps you individualize to kids.”

Instead of focusing on standardized testing, it’s more important to see how a student improves and grows during the school year, she said. Flexibility in the classroom, including when and how a test is administered, can also make a difference.

“I think the public would be really surprised to know how few questions are on a standardized test,” Cigler-Nelson said. “I mean, there's a lot riding on 40 to 50 questions. And if you didn't eat breakfast that morning, if your parents are in the middle of a divorce, and it's one of those two days, that's a lot, it's a lot to ride on something.”

One of Cigler-Nelson’s goals in the classroom, where she teaches students from all different walks of life, is always to challenge the worldview of her students. “To me the point of education is fundamentally not standardized tests,” Cigler-Nelson said. “(It’s) can you go into the world and be a critical thinker? Can you not just take things at face value? And can you reevaluate based on new information? That is what living in this world that they inheriting is about.”

To fit that goal, Cigler-Nelson incorporates a unit on civil rights into her class, where students learn and explore African American civil rights, Chicano Civil Rights, and the LGBTQ rights movement. Her students research, write about, discuss and examine the perspectives of these groups through a variety of assignments, including reading narratives and writing first-person journals.

The opportunity to see students who identify as members of underrepresented groups feel heard and valued in the classroom is always exciting, Cigler-Nelson said. “That's obviously always a goal, in English class at least, to be sure that you are challenging people's worldview, while at the same time helping them validate themselves as people,” she said.

Topics like that often bring up difficult conversations.

"Part of being an English teacher really hinges on kids being able to say stuff to you,” Cigler-Nelson said. “And if that environment is not cultivated, it doesn't work. Because as an English teacher, you're going to read things that are difficult, not just the reading itself, but the subjects that they deal with. And then if you do not have an environment for people where they can say what they think, then you have a real problem.”

Conversations like those have helped her create a community that extends beyond the classroom walls. Every summer, it even extends into her home, where former and incoming students gather to discuss literature and other topics in an informal book club.

The book club, which doesn’t have an official name, has been around since the very beginning of Cigler-Nelson’s teaching career. She started it as a way to encourage her students to read over the summer. Now, it's a combination of incoming students, recent graduates and students who have been out of school for years. This summer, one of its oldest members was 25.

It was one of her best choices in her nearly 25 years of teaching, she said. Not only does it keep students reading, but it keeps them connected to the community she’s built, even long after they’ve left the four walls of her classroom.

“I'm really glad that I made a choice like that, that I did something that kept me in their lives and kept them in my life,” she said. “Because …what better gift is there for a teacher? I mean, it's a huge gift to me to have that. It's one of the great intangibles of which there are many.”

“Those are the kinds of things that are hard to walk away from,” Cigler-Nelson said. “And when the job is difficult and frustrating and challenging, those are the kind of moments that make it amazing at the same time and I feel really lucky that I get to have those with a certain level of frequency.”

As a first-year teacher, there’s more intangibles than I can imagine. Talking to an accomplished teacher like Cigler-Nelson makes it easier to focus on the most important things - building those relationships that extend past the 48 minutes they’re in your classroom each day.

About Allie Crome

Allie Crome is a May 2019 graduate of Emporia State University and the former managing editor of the campus newspaper, The Bulletin. She now teaches high school at Silver Lake, Kansas.

Gallery

View

View View

View View

View View

View