(Mineral) Spring Fever Hits Kansas

Convinced coal lay below his land, a young stone mason named Walter Sharp sold his house to raise enough money to hire a well-driller to find that sweet vein under his property near Marion in southeast Kansas. For reasons now lost to history, the drill stopped after 100 feet and Sharp found nothing but murky water. Determined to salvage his life savings, Sharp began figuring out whether he could make money off the water seeping into the hole. After a friend told him it smelled like water from a mineral springs he had been to, Sharp began bottling it and selling it as a medicinal solution.

This “Spring Fever” led flocks of Marion County residents to Sharp’s land, and he erected buildings and facilities on the site to accommodate them.

In the 1880s, mineral springs rose to the top of the American tourist imagination. Due to their alleged healing qualities, promoters built hotels and resorts for families across the country near natural springs. This “Spring Fever” led flocks of Marion County residents to Sharp’s land, and he erected buildings and facilities on the site to accommodate them.

Enter Dr. George L. Piper, an experienced physician and, as the Marion Record reported, an “intelligent affable gentleman.” Dr. Piper heard the spreading buzz about Sharp’s spring and offered to lease it from Sharp, investing much of his own money to outfit the spring as a full resort. Chingawassa Springs was born.

Opened in summer 1888, and connected to Marion and the rest of Marion County by a new, taxpayer-funded rail line, the resort promised to bring a tourist-driven spark to the region. On March 16, 1888, the Marion Record wrote, “The Record grows more and more confident that this mineral water is to make Marion famous as a sanitarium, and widely noted as a health resort.”

Dr. Piper promised that his Chingawassa waters cured “Rheumatism…Paralysis, Skin and Blood Diseases, Kidney and Liver complaints, Chronic Constipation, Hemorrhoids, Catarah, Nervous and General Debility, and Female Weakness.”

Confidence spread that Chingawassa Springs would be a boon for the town, stoked in no small part by Dr. Piper himself. On July 27, 1888, Piper wrote a letter to the Record claiming “We now have the Sanitarium fitted up ready.” In the letter, Dr. Piper promised that his Chingawassa waters cured “Rheumatism…Paralysis, Skin and Blood Diseases, Kidney and Liver complaints, Chronic Constipation, Hemorrhoids, Catarah, Nervous and General Debility, and Female Weakness.”

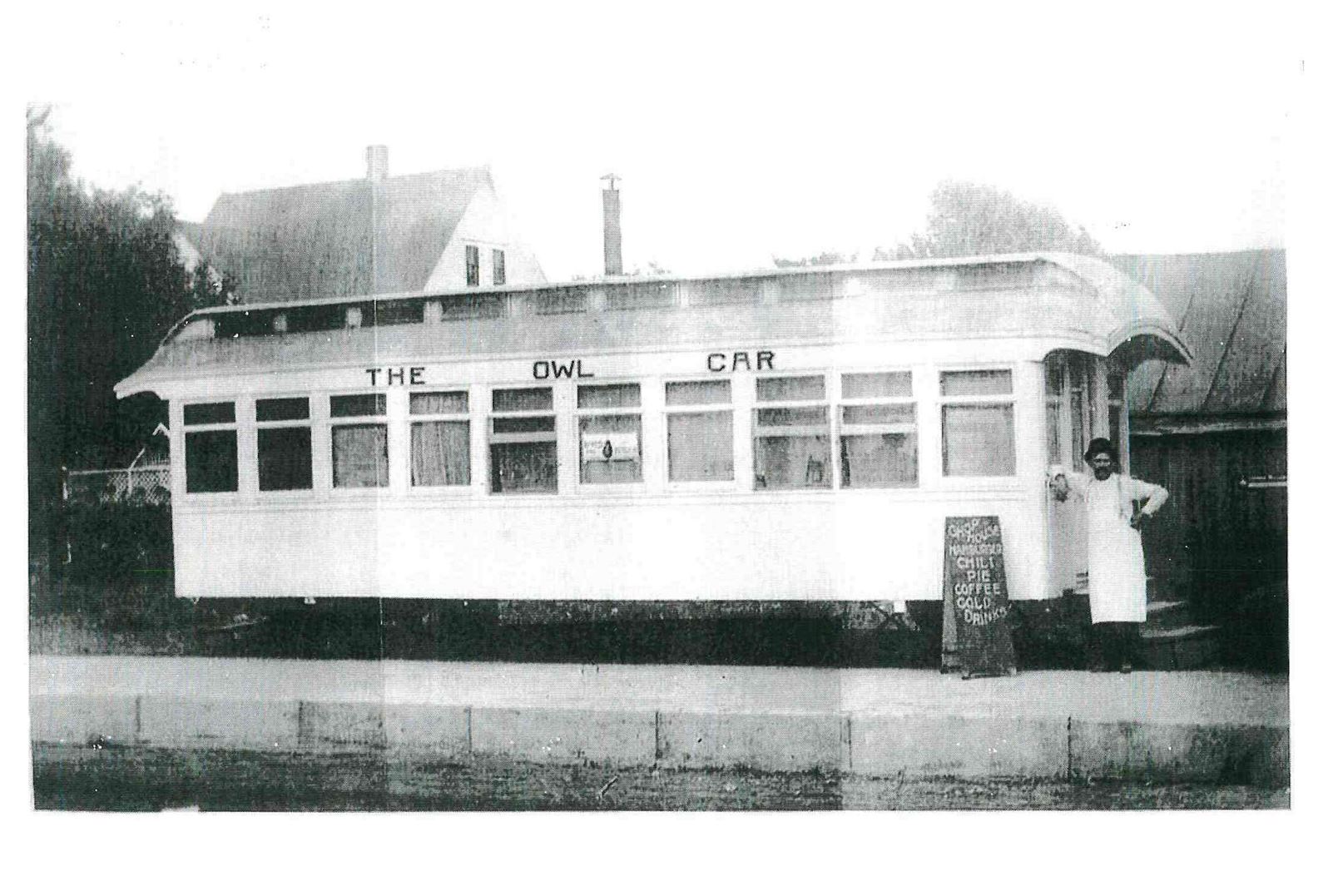

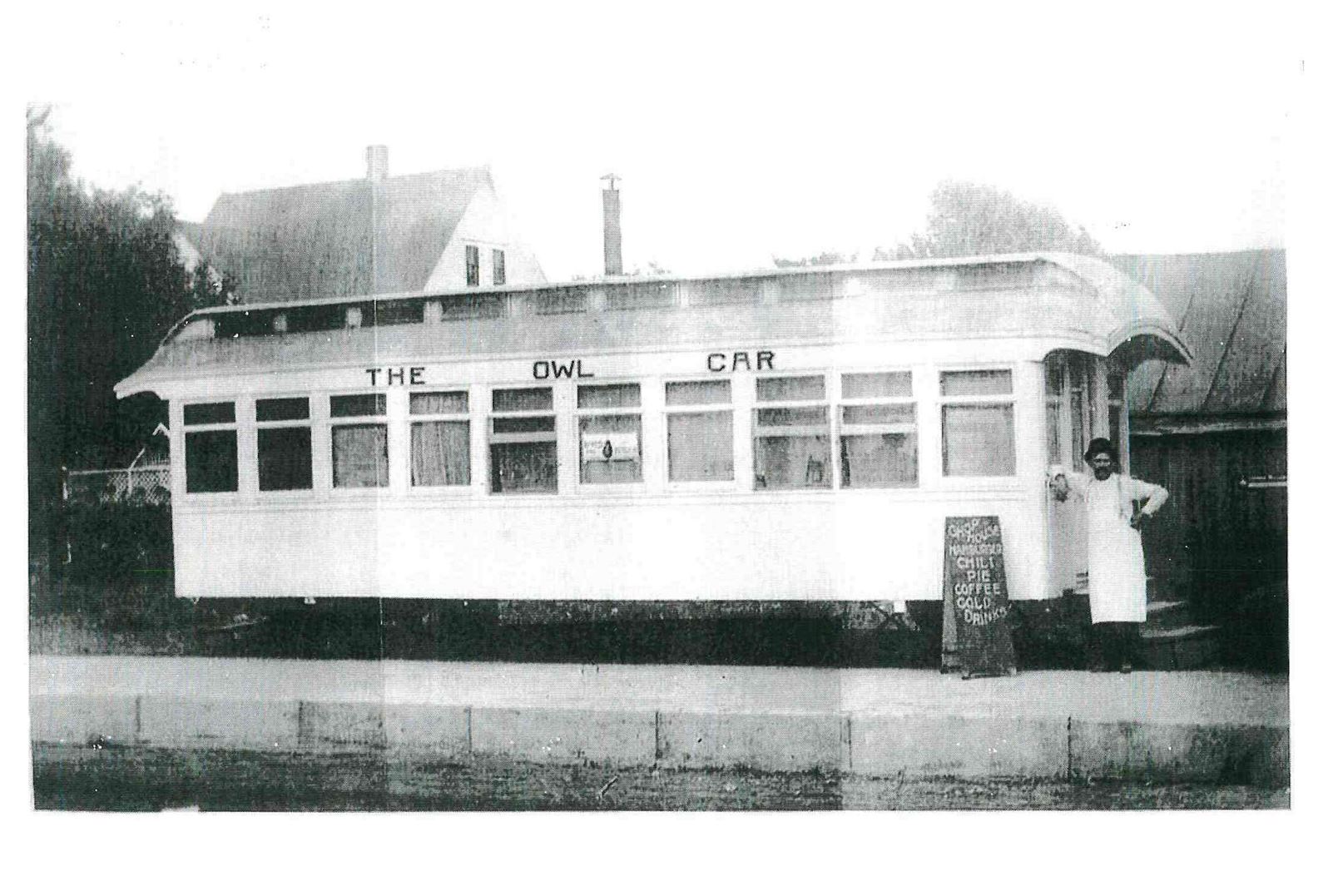

While the first season of the resort proved a success, the novelty soon wore off, and it became clear that Marion’s population of just over 3,000 was not large enough to support continued operation of the spring. After three or four years, Chingawassa Springs was a thing of the past. Bill Root, whose farm lay 10 miles east of Marion, bought the railroad cross-ties to use as fence posts. The railroad cars became locations for a dentist and the Owl Lunch Stand.