Don't Forget Broughton

In 1966, government bulldozers arrived in Broughton, near Clay Center in north central Kansas. The engineers operating the bulldozers carried maps, which marked almost every house in town with circles. The circles indicated homes slated for demolition. The town emptied of people long ago, and now it was about to be empty of houses, too.

The dam created Kansas's largest lake, Milford, an "inland sea."

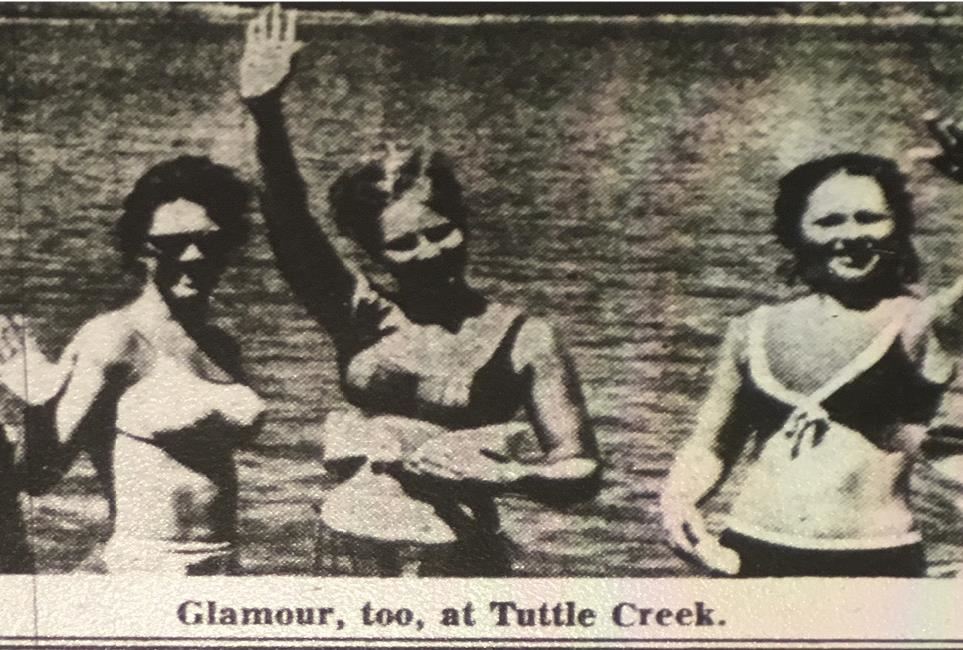

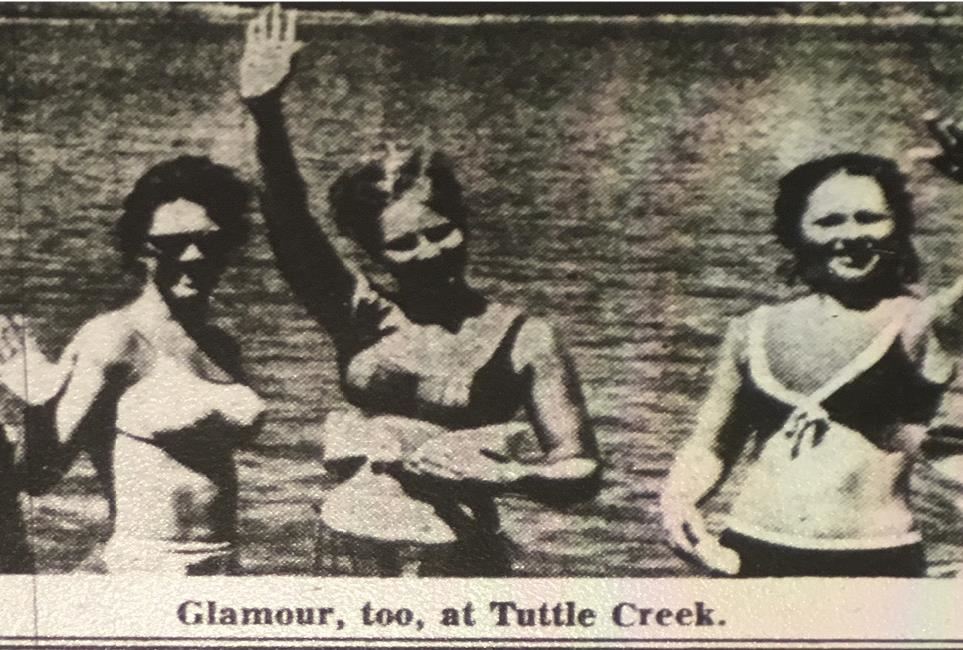

From 1962-1966, the Army Corps of Engineers built a dam on the Republican River near Junction City. It created Kansas’s largest lake, Milford, an “inland sea.” Newspaper articles featuring attractive swimmers in bikinis promoted the idea of the new dam promising aquatic recreation and “glamour, too.”

The dam project arose as memories of 1951 still lingered in the minds of many riverside Kansans. The flooding that year devastated so many communities that it spurred the government to action on flood control. Add that to a New-Deal-inspired, Eisenhower-driven, anti-communist faith in big government projects and Kansas saw two major dams arise together within the span of a few years: Tuttle Creek and Milford.

“large scale development and public works were supposed to be for the benefit of the public, but in practice, important community livelihoods as well as linkages to significant human history were destroyed in the name of ‘progress.’”

Still, the Milford project inspired fierce opposition, especially from those in the towns that would have to move or be abandoned. The book Broughton, Kansas: Portrait of a Lost Town explains, “large scale development and public works were supposed to be for the benefit of the public, but in practice, important community livelihoods as well as linkages to significant human history were destroyed in the name of ‘progress.’” In order to prevent future floods in larger, downstream cities like Junction City and Manhattan, purposeful flooding would erase Broughton and 13 other smaller towns.

The people of Broughton knew what was coming. They were located in the flood plain for the Milford Dam. They saw it plainly on the planning map hanging in the post office: if the dam collapsed, no more Broughton. A similar project took shape in the creation of the nearby Tuttle Creek dam, and towns much like theirs were scrubbed from the map to make room for its reservoirs and floodplains. One resident said, “We all knew, when it came to be Broughton’s turn […] we knew we wouldn’t win.”

The post-war trends that saw young people fleeing small towns for big cities and college affected Broughton, too. Thus, the population of the town declined throughout the 1950s. By the time 1965 rolled, with its scheduled bulldozers rolling in as well, few families remained. Among them were the Bauers, whose ancestors settled the area in 1868. According to Broughton, Kansas: Portrait of a Lost Town, “the Bauers stayed so long on their land that they eventually received a ‘condemnation order.’ Family members still recall this bitterly […] ‘Many nights my father lay awake trying to reach a decision,’ Diana Bauer wrote in 1965.” The family eventually moved to Nebraska in an attempt to start anew. A few short months later, the bulldozers aimed their plows at their homes.

Kansas State history professor M.J. Morgan wrote that, “three general themes” encapsulated Broughton’s character. First were “psychological and social orientations”, based on proximity to the Republican River. The river provided fertile bottomland for farming. It also helped create a close-knit community through water recreation such as summer swimming and winter ice-skating, and had helped the town persevere through hardships, namely floods.

Second was “an impressive degree of human mobility” in counterpoint to the small core group of Broughton residents. For example, fifty young men from this tiny community served in World War II.

Third and perhaps most important was “a high degree of inclusion for people who were often viewed as ‘other,’” including African Americans, immigrants, and even Gypsies. Mark A. Chapman grew up there, eventually going to Kansas State University and then on to Texas where he became a wealthy businessman.

Chapman, thinking back on Broughton from his adopted home of Texas, decided to do something about the as-yet unrecorded history of his town, which at that point was only visible as ruins in the woods. In collaboration with Kansas State University, he founded the Chapman Center for Rural Studies (http://www.k-state.edu/history/chapman/).

Their first project was Broughton, Kansas: Portrait of a Lost Town, a book produced as collaboration between center director M.J. Morgan and her students. The book is a lively slice-of-life history that brings the once-forgotten town to life in its pages.

After finishing the Broughton book, Chapman and the Chapman Center decided to widen their focus, researching and documenting all kinds of lost or forgotten Kansas towns. The Chapman Center website provides a treasure trove of forgotten Kansas history.

All told, 14 towns were moved, razed, or abandoned to make way for the Tuttle Creek and Milford Dam projects.

To learn more about how water shapes the lives of Kansans, be sure to visit Water/Ways Smithsonian Institution traveling exhibition and the local exhibition, SubMerged, on display at the Geary County Historical Society & Museums from January 6 to February 18, 2018 and at the partner exhibition in Our Relationship with Water opening at the Rice County Historical Society in Lyons on January 29, 2018.