Big Idea: Confronting the Legacy of Indian Boarding Schools

January 5, 2022

By Eric P. Anderson (Citizen Potawatomi Nation), Professor of History in the Indigenous & American Indian Studies Program at Haskell Indian Nations University

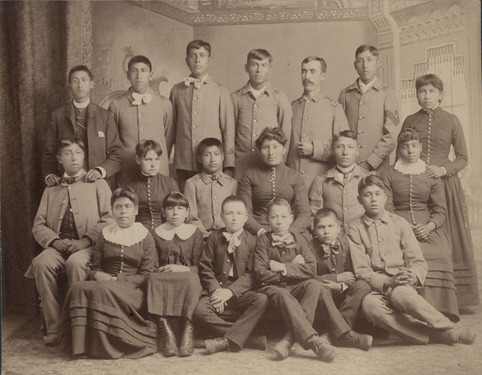

When Haskell Institute opened in 1884, it was known as the Indian Industrial Training School at Lawrence and was among the first of the U.S. government’s off-reservation boarding schools for American Indian children. Based on Richard Henry Pratt’s Carlisle School in Pennsylvania, with its creed to “Kill the Indian, Save the Man,” Haskell was one of a network of boarding schools that worked to destroy Native cultures by enforcing Euro-American standards of appearance, thought, and behavior. The cultural and moral injury inflicted by these schools impacted generations of Indigenous families and still reverberates today.

Indian boarding schools have been in the news this past year because of the discovery of mass graves of children who attended parallel residential schools in Canada. These discoveries have prompted U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland (the first Native American to serve in that capacity) to call for a thorough investigation of this history. By bringing greater awareness to this period of our past, we stand to learn from the troubled relationship between indigenous Americans and the dominant society and, ideally, begin a process of healing.

Federal boarding schools, of which Haskell would become the largest by the early 20th century, expected students to conform by speaking English exclusively; practicing Christianity; and adopting Western ethics of work, family structure, and other modes of thinking largely foreign to Native people. This assimilationist model, which held sway well into the 1930s (and arguably far beyond), thus affected tens of thousands of American Indians. Daily life for students meant enduring homesickness in a cold, institutional environment that adhered to a strict military regimen, accompanied by the very real threats of disease and death that became hallmarks of these schools. For their families, separation from these children constituted an unspeakable sorrow, one often compounded by the return of young people who, after years away at school, could no longer speak the language or understand the cultural practices of their elders.

Haskell Institute students, c. 1890. Image courtesy of kansasmemory.org, Kansas Historical Society.

Eventually Haskell Institute evolved from its initial rudimentary academic focus into a high school, then a college, to finally Haskell Indian Nations University. Although the focus and curriculum of boarding schools softened over time, the costs have run deep, and the effects are widespread. Today, Indian Country is still reeling from the legacies of policies put into practice so long ago. Nearly every Tribal Nation is struggling to maintain (or regain) assaulted languages, ceremonies, and beliefs. Cycles of dysfunction resulting from the rampant mental, physical, and sexual abuse that took place at these schools are a continuing challenge. Family dynamics, which were disrupted by the constant separation and alienation of this period, have suffered. A lingering historical trauma remains.

For these reasons, it is vitally important to reckon with this chapter of the American past. To do so will be difficult, and often painful, both for Native and non-Native people alike. However, this is also an opportunity to understand a shared history and to build bridges to a brighter mutual future.

About Eric P. Anderson

Eric P. Anderson (Citizen Potawatomi Nation), Professor of History in the Indigenous & American Indian Studies Program at Haskell Indian Nations University.

Spark a Conversation

- READ Adams, David Wallace. Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875-1928 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1995).

- WATCH In the White Man’s Image (Director, Christine Lesiak), PBS: American Experience, 1992.

- VISIT Haskell Indian Nations University Cultural Center and Museum in Lawrence, Kansas. Contact the cultural center for hours of operation during the pandemic.