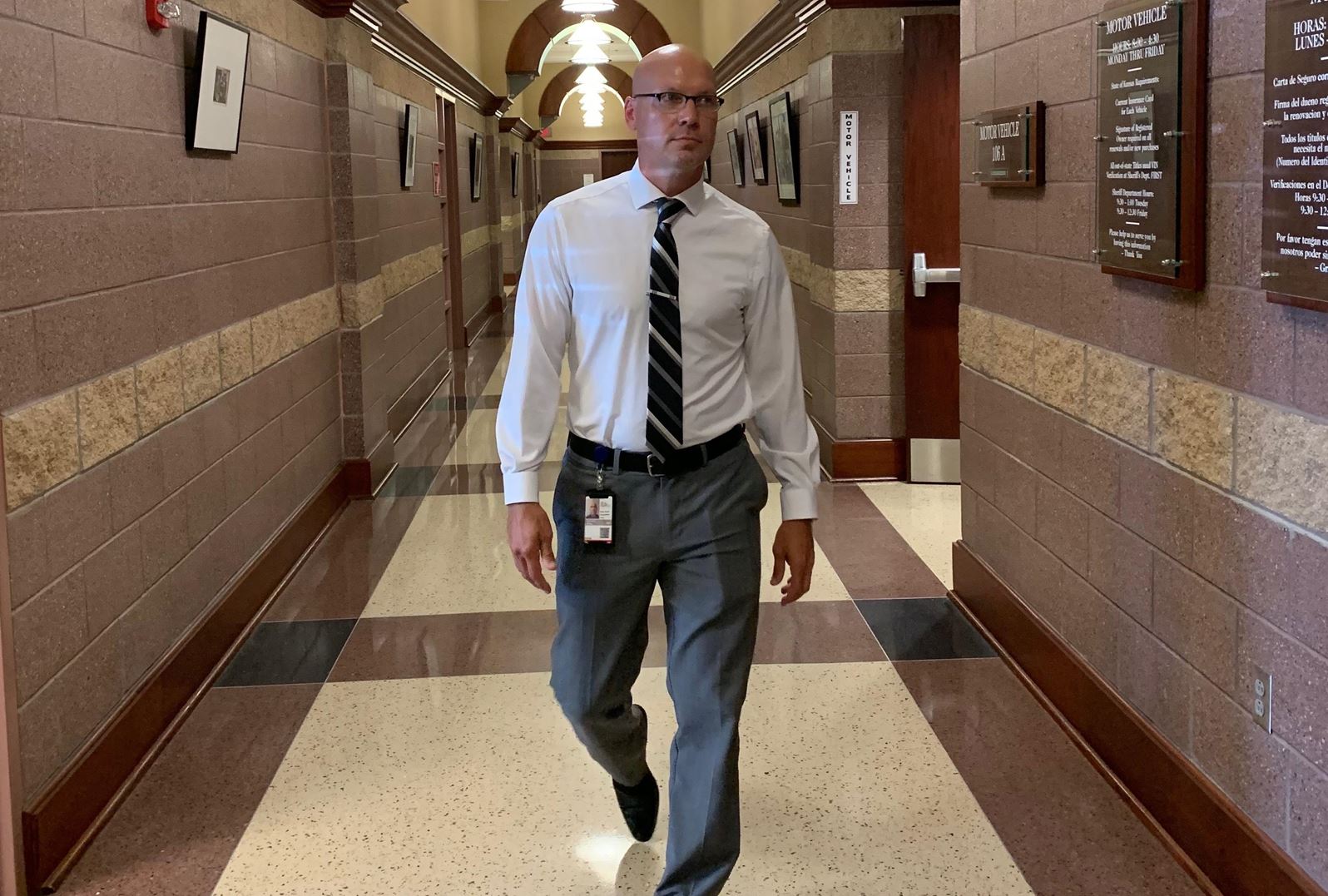

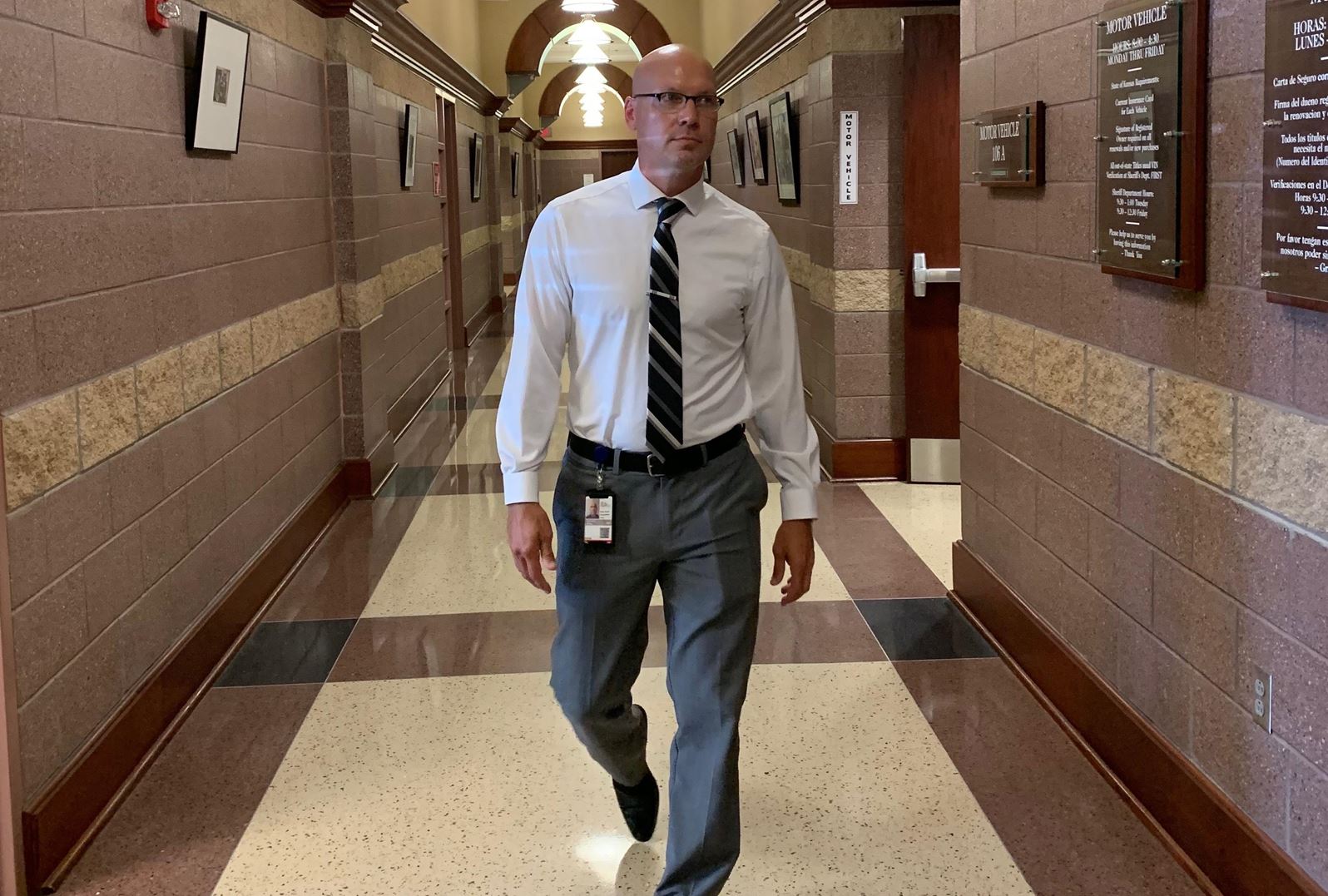

Finding Humanity in Those Who Need it Most

November 1, 2019

This essay is part of the Ad Astra: Working Hard in the Heartland initiative featuring the stories of working Kansans.

Story and Photos by Katelynn Donnelly

When Steve Willis was a child, he ocassionally experienced stress, but he always counted on one thing growing up in Salina in the 1970s: family dinner.

Even though his parents divorced when he was four, and he felt the typical childhood stress of living in a blended family with several step-siblings, he always looked forward to family dinner. It was nice just to talk about his day, he remembers.

Much of that changed when Willis was 10. His step-brother, he said, started going a different direction. The step-brother was about the same age, but chose a different crowd. Willis knew it meant trouble.

Eventually, his step-brother was arrested on felony drug charges and is now supervised by the Kansas Department of Corrections. Willis is reluctant to talk about the step-brother, and requested that he not be identified by name in this story.

A no-nonsense, yet kind spoken individual, Willis’ passion for keeping those in and out of the correction system safe is made apparent at first meeting. He explains the connection between the safety of the community and the most effective ways to help the 120 individuals on probation in Lyon County. Statewide, the Kansas Department of Corrections supervised 5,746 individuals on parole or some other form of supervision, according to a report provided by Cheryl Cadue, a spokesperson for the Kansas Department of Corrections.

All Kinds

Willis, the Director of Community Corrections, oversees the intensive adult and juvenile offenders in Lyon County, Kansas. He knows people make bad choices and learned from his experience that a major part of helping them is through cognitive reconstruction.

Willis said, “Imagine just being frustrated your entire life and not knowing what you’re doing and not having a good plan and always feeling like you’re messing up and that’s who we work with a lot.”

He recalls one case in November of 2017 involving a man that was a potential danger to the community. The offender was an active user of meth and suffered from psychotic episodes. As law enforcement arrived with the intent to arrest the offender, the man pleaded that jail was not the answer and Willis’ team agreed. Instead, they granted him house arrest.

The mental health department reviewed the case and prescribed the offender new medication. He graduated from drug court with zero violations and became a mentor to other offenders.

We think about that and we use that case a lot because we had enough information and enough cause to arrest him,” Willis said, “ and he would have been revoked and sent to prison and left the community for 3-4 years and came back with the same problems still.”

“Imagine just being frustrated your entire life and not knowing what you’re doing and not having a good plan and always feeling like you’re messing up and that’s who we work with a lot.”

Keeping His Team Safe

However, some cases do not have such a happy ending. Willis said although the majority of the relationships between law enforcement officers and offenders are positive, the staff remain exposed to safety risks doing field work.

One improvement Willis made in Lyon County since he began working there three years ago is requiring that a bullet proof vest be worn when entering an offender’s home. He also mandates staff to have TASER certification if they do surveillance checks as night. Defensive tactics training is no longer optional.

Home visits are complicated, Willis said. More often than not other people living in the homes of the offenders do not want law enforcement coming around.

Although the work is well intended, it still makes people upset. He said, “You’re making a lot of people angry, especially in the first few months where they feel like there’s not a problem. Until they start recognizing themselves that there’s a problem they’re angry at you.”

Willis said much of the behavior that causes people to be incarcerated is a result of drug use.

Of the 120 adult offenders, 85 percent have a drug addiction but only 60 percent of the population are in for a drug-related offense. Meaning many of the behaviors are driven by the need for drugs such as stealing or acts of violence.

“The biggest problem for us is the drug use. If we could find a way to limit drug use or decrease some of that stuff we would see less criminal behavior but right now drugs in the community are so bad and it’s so easy to access that most of the people in our program have a drug addiction.”

Not Evil, Just Struggling

Willis believes the drug addiction can be attributed to a lack of problem solving skills. He said it is important to remember the people in the corrections system are not bad people, they are just struggling. The job of community corrections staff is to help offenders get the tools they need.

“Our goal is to model good behavior and to help them see where behavior can change,” Willis said, “So we’ll continue to do that so that at some point they understand there is some support for them and there is a better way to manage their life.”

For someone that is of the greatest risk it takes about 250 hours to change cognitive structure, Willis said. Over the course of 16-36 months offenders participate in one or several of the programs tailored specifically to the needs of the offender.

“There’s a different mentality with the people we work with here that if you continually sanction and contain without any restructuring involved with it they’ll always feel like a victim in that situation,” Willis said, “we’re here to help and we’re helping people who we have an opportunity to help.”

It is much more than policy work, it is truly fixing a life. Willis believes the job requires empathy to see the people for their struggle and not their actions.

With this difficulty comes a lack of recognition for the work done. Willis said, “Because the person is known as the convicted felon that stigma is always where the perception is...the goal is to help those probationers that are in our service to build better lives."

The staff makes the choices of removing offenders from the community when they recognize that some people can’t overcome their backgrounds or criminal tendencies, Willis said. No matter how many difficult decisions he makes in a day, Willis said his goal is to always go home with a positive attitude. “I had tough conversations but it was still a conversation and we at least addressed some things and while they didn’t like it, tomorrow we’ll come back and start again.”

About Katelynn Donnelly

Katelynn Donnelly is a senior elementary education major at Emporia State University. She is assignments editor for the campus newspaper. Her hometown is Kansas City, Missouri.